Tucked off Route One, the Ice Pond Trail loops through 76 acres of woodlands, wetlands, and undisturbed wildlife habitat. Forest creatures—fox, deer, fisher, raccoons, bear, even moose—have been spotted. There are stands of white birch, alder, black spruce and more. With some blueberry patches, a cranberry bog, and wild strawberries, there’s a cornucopia of fruit for wildlife. CNLT named it The Ice Pond Preserve in honor of its pond, which once provided ice for folks living in this area.

Located near the Pettengill Preserve and the Old Pond Railway Trail, the Ice Pond Property is in line with our vision of local conservation in the area and fits perfectly with our mission: providing as many opportunities as possible for people to get out onto the land while preserving corridors of undeveloped land for wildlife habitat and protecting the area’s rural heritage.

Ice Pond Management Plan

by Josh Ferris, Stewardship Coodinator

Property Description

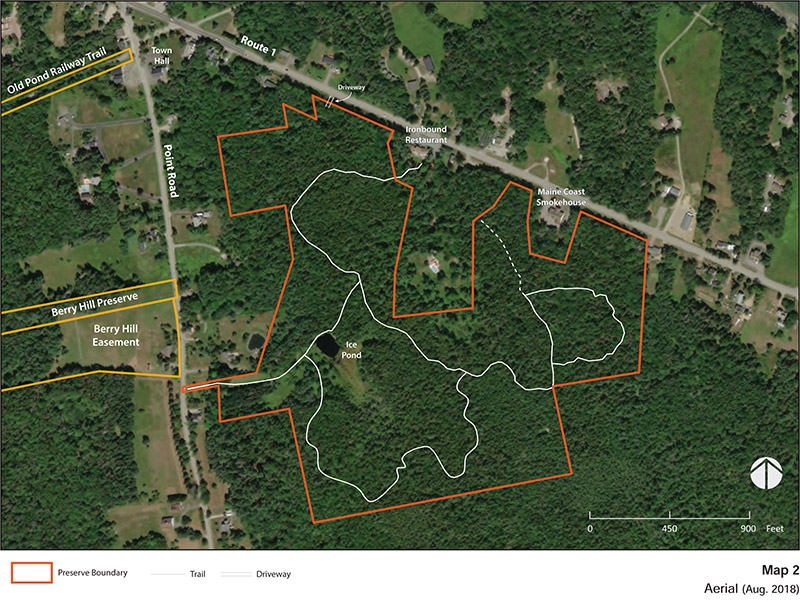

The Preserve consists of approximately 86 acres of spruce-fir forest (Map 2). The boundaries of the Preserve are irregular, with a perimeter of approximately 2.3 miles. The Preserve has three segments of frontage on Route 1 totaling approximately 1,052 feet. The Preserve has 30 feet of frontage on the Point Road, which provides a signed trail head.

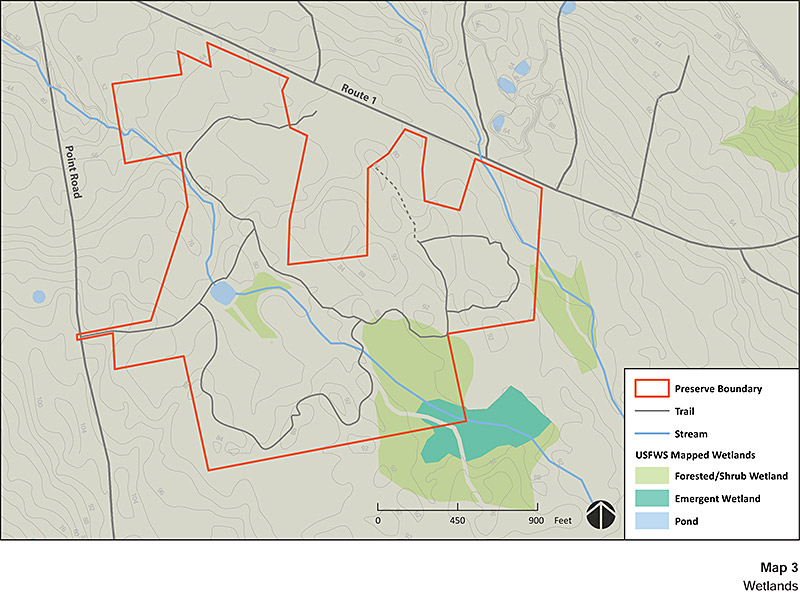

The topography is gently sloping with elevation ranging from approximately 50 to 90 feet above sea level. The US Fish and Wildlife Service has identified about 7.5 acres of the Preserve as forested /shrub wetland (Map 3).

Access

Primary access is provided by the parking lot on Route One, west of Ironbound Restaurant. There is no parking at the trailhead on Point Road and please do not park on the road there.

The Preserve has 1.6 miles of trails that are open for walking and biking. Bog bridging provided through wet areas is constructed as double, parallel laid planks.

Natural Resource Summary

Geology

The geology of Crabtree Neck is comprised of the Ellsworth Formation. This formation started around 500 million years ago as sediment and volcanic materials deposited on an ancient ocean bed. Plate tectonics forced the crust of this ocean beneath an adjacent plate. As the sediments were folded and uplifted, this material metamorphosed into schist and gneiss. Ellsworth Schist is dark green or gray, complexly folded and streaked with lighter colored layers of quartz and feldspar. During the most recent ice age, the schist bedrock was scoured by glaciers that were over 3,300 feet thick. The glaciers smoothed the landscape while leaving behind an unsorted mixture of clay, sand, gravel and boulders known as “glacial till.” In some places, especially along the northern margins of Crabtree Neck, the glacial sediments were deposited in marine environments where they were influenced by marine processes (i.e., tides, currents and changing sea levels). These sediments are referred to as glaciomarine sediments that along with glacial till comprise the primary sources of surface geology on Crabtree Neck. As the glaciers melted, the weight of the ice was lifted and the earth’s crust, which had sunk under the weight of the thick ice, gradually rebounded. Coastal Maine rose above sea level between 12,000 and 11,000 years ago (Gilman, et al. 1988). As the land rose, the sea retreated to about 180 feet below the current sea level thus exposing lands far beyond the coast we see today. Gradually, as the continental ice sheet continued to melt, the sea level rose. Around 2,000 years ago, the rising ocean reached the present level, and the current coastline of Crabtree Neck was established.

Soils

Soils found on the Preserve are described by the United States Soil Survey as being formed by glacial activity. The parent material (original geologic bedrock or deposit) from which these soils have formed is primarily glacial till and glaciomarine sediments. Portions of the Preserve are mapped by the Soil Survey as Tunbridge-Lyman complex and Peru fine sandy loam, which are classified as prime farmland (Map 4). Prime farmland, as defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is land that has the best combination of physical and chemical characteristics for producing food, feed, forage, fiber, and oilseed crops. The Preserve also has areas mapped as Adams loamy sand and Lamoine silt loam, which are classified as Farmland of statewide importance. This classification of soils indicates soils that that are nearly prime farmland and that economically produce high yields of crops when treated and managed according to acceptable farming methods. The remaining soils on the Preserve are identified as not prime farmland.

Ecology and Habitat Types

The Preserve provides upland habitat for the tidal estuaries of Old Pond/Youngs Bay, which is part of the Taunton Bay Focus Area of Statewide Ecological Importance identified by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. The Preserve provides watershed protection as well as foraging and dispersal habitat. The Preserve drains to a slough that feeds into Old Pond. The low lying lands surrounding this slough are expected to provide for marsh migration as sea levels rise.

Of the natural community types classified by the Maine Natural Areas Program, three are present on the Preserve. Most of the Preserve may be characterized as Lower-elevation Spruce – Fir Forest.

Lower-elevation Spruce – Fir Forest

This is the most common forest type, dominated by red spruce with some balsam fir and white pine. The understory is sparse with balsam fir and red spruce in more open areas. Ground cover is a mix of bare conifer litter and patchy to full bryophytes (three-lobed bazzania and red-stemmed, plume, and hair cap mosses). In sunnier areas, bracken, sheep laurel and reindeer lichen make up a portion of the understory. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has identified about 7.5 acres of the forest on the Preserve as forested wetland.

At the western edge of the Preserve, near the Point Road trailhead is a half-acre area that was planted exclusively with fir. A smaller stand of Norway spruce is located at the trailhead.

Alder Thicket

This shrub dominated wetland is located in wet areas near the Ice Pond, and is dominated by speckled alder, with an herb layer of cinnamon and sensitive fern, sedges and bluejoint grass.

Tall Grass Meadow

Tall Grass Meadow is located in wet areas near the Ice Pond and mixes with alder thickets. It is comprised primarily of bluejoint, with spirea, aster and meadowsweet.

Low Sedge Fen

Just upstream of the Ice Pond is a vegetative community of sphagnum moss substrate with sedges, cranberry, and cotton-grass. This area may have formed as a result of the construction of the pond, which dammed the flow of the stream. This habitat transitions to a cattail marsh, alder thicket and the spruce-fir forest beyond.

Wildlife

Wildlife that frequent the preserve include deer, fox, coyote, bear, fisher, muskrat, weasel, porcupine, snowshoe hare, red squirrel, turkey, grouse, and barred owl. Nesting birds include chickadees, warblers and thrushes.

Invasive Species and Control Options

No invasive species have been identified on the preserve.

Land Use History

The first humans arrived in Maine as the glaciers retreated about 12,000 years ago. These Paleoindians found a landscape of grassy plains and tundra interspersed with willow, alder and spruce populated with wooly mammoths, mastodons, caribou and giant beavers. Over time the habitat of Maine shifted from plains to boreal forest. During this time, around 9,500 years ago, the cultural attributes associated with Paleoindians (such as Clovis spear points) disappear from the archaeological record. The Archaic Period (9,500 to 3,000 years ago) found people adapting to a warming climate that brought a forest of mixed hardwoods and softwoods. As the environment stabilized, small bands settled into a seasonal pattern of regular hunting, fishing and gathering sites. Archaic people relied on an increasingly diverse variety of animals (including smaller mammals, anadromous fish, shellfish, and marine mammals) and plants (roots, seeds and nuts). During the latter part of this period, the Red Paint People appeared on the coast (5,000 to 3,500 years ago). This culture gained its archaeological identity from the iron oxide used to cover grave vaults, which also included ritual slate spear-points, lance tips, charms, amulets and ornaments. The Ceramic Period (3,000-500 years ago) began with the introduction of pottery as well as agriculture and the birch-bark canoe. During this period, people increasingly relied on coastal and marine resources. In the 1500s and 1600s, when Europeans first landed on the coast, Maine was settled by the Wabanaki people. Today, the tribes of Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Mi’kmaq, Maliseet and Abenaki make up the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Traces of the Wabanaki people and their ancestors have been found on Crabtree Neck. Shell heaps found near the present-day locations of Tidal Falls (aka Sullivan Falls) and Riverside Cemetery and at a point off Jellison Cove Road, mark sites where Indians camped repeatedly for many years and discarded clam shells.

Europeans began arriving on the coast of Maine in 1524, with both the English and French making claims to Wabanaki territory. This led to a long period of conflict between the two nations, their competing colonies, and the Wabanaki. The Wabanaki were greatly reduced by waves of disease spread by the Europeans, their numbers declining from about 20,000 in the early 1600s to around 900 in 1760 (Penobscot Marine Museum, 2012). George Varney, in his Gazetteer of the State of Maine, states that there was evidence of an old French settlement at Waukeag[1], an old place name for the Sullivan area. Varney recorded that “an earthen pot, containing somewhat more than $400 in French coin was dug up. They born the date of 1725”. Varney also states that indications of French settlements were found at Crabtree’s Neck (Varney, 1886). Between 1675 and 1763, a series of six wars were fought between the British and the French/Native Americans. The final war, the French and Indian War was ended by the Treaty of Paris in 1763. Under the treaty, France abandoned all claims to territory in North America. This cleared the way for Anglo-American settlement of Downeast Maine (Penobscot Marine Museum, 2012; Maine Historical Society, 2010).

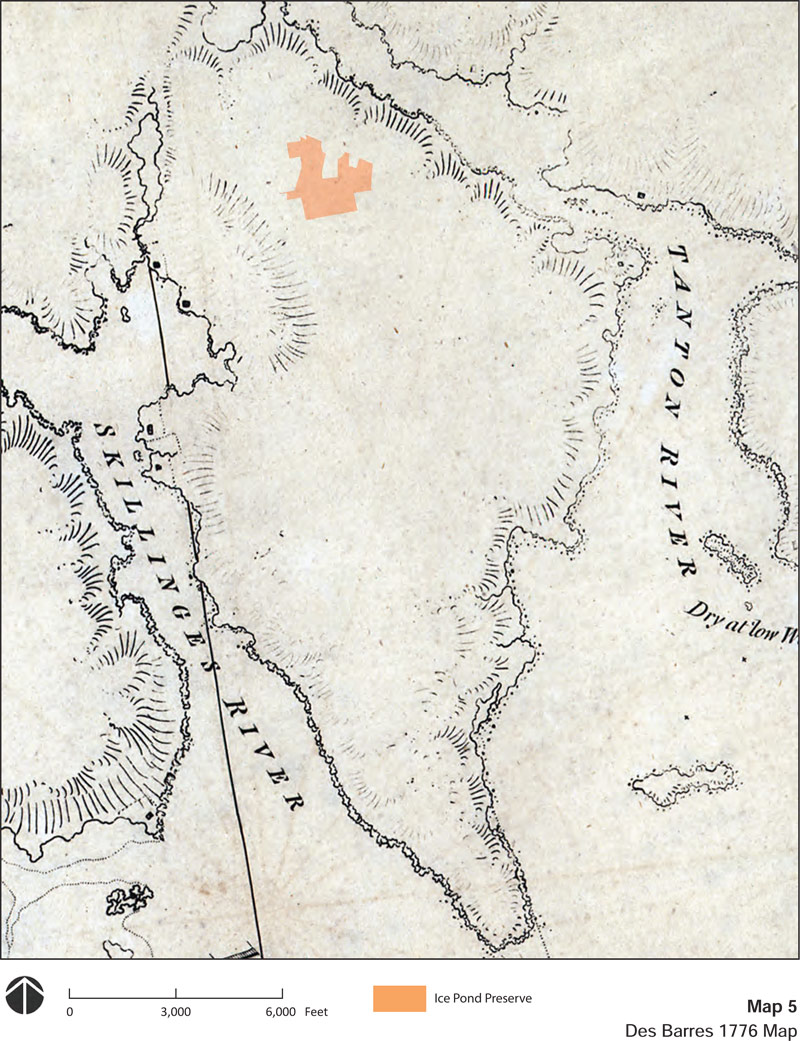

The first permanent Anglo-American settlement of Crabtree Neck began in 1764-65. The first settlers consisted of Captain Agreen Crabtree and Philip and Shimuel Hodgkins on the Skillings River, where they built a sawmill and grist mill near Hills Island. A map of the region published in 1776 shows six settlements on Crabtree Neck, four along the Skillings River and two on Taunton Bay (Map 5). Crabtree Neck was initially part of the Town of Sullivan, which was incorporated as a town of the State of Massachusetts in 1789. Maine seceded from Massachusetts in 1820, and the Town of Hancock was subsequently incorporated in 1828.

The Town of Sullivan was surveyed in 1803 under order of the General Court of Massachusetts, with settlers provided properties of 100 acres for a payment of $5.00. By superimposing the current boundaries of the Preserve on the 1803 plan of settlement, the current Preserve contains portions of the lots settled by Stephen Merchant, Moses Abbot, and Rueben Abbot (Map 6).

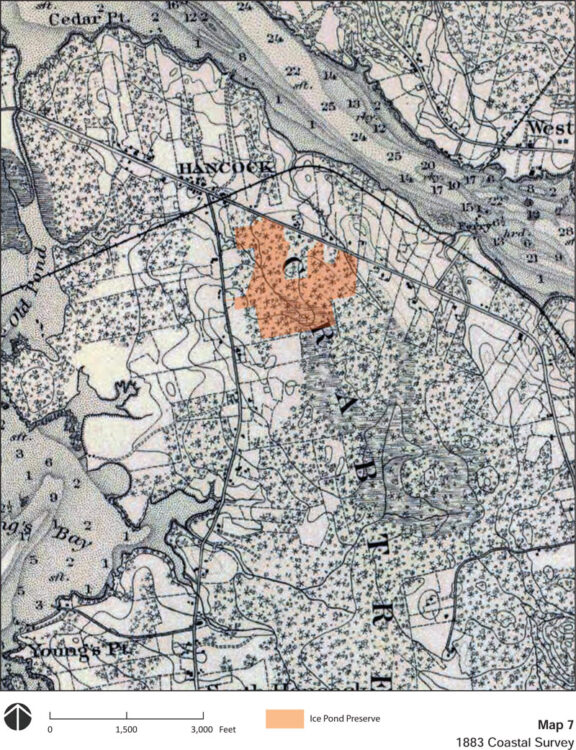

The 1883 Coastal Survey shows the Preserve as being almost entirely forested (Map 7). Subsequent USGS topographic maps show no development on the Preserve. An aerial from 1956 shows one building (probably a home) on the Preserve approximately 500 feet northwest of Le Domaine (Map 8). All that remains is a culvert and unimproved driveway. The 1956 aerial shows the Preserve as mostly forested. The darker areas of forest appear to be mature red spruce forest, which persists to this day. The lighter area of forest in the southeastern portion of the Preserve appears to be young regenerating forest. The area south and west of the pond are open field. A portion of this area was subsequently developed with a fir plantation.

The Ice Pond was used as a source of ice prior to the innovation of home refrigerators. It is not known when the pond was developed. It is not a natural feature, but was excavated and a dam and spillway installed. According to Sandy Phippen, in the 1950s the pond was owned and maintained by Russell and Sylvia Young who lived at 76 Point Road in a home that still stands very close to the road (because it was once a store). Sylvia Young organized the youth group at the church and they hosted skating parties on the pond. According to Renata Moise, her father Bill Moise worked for Russell Young in the 1950s cutting ice from the pond. Both Sandy and Renata remember a large sawdust pile north of the pond where a building had formerly been. Sawdust was used to insulate the ice to preserve it through the year.

[1] Varney (1886) identifies Waukeag as an Indian name for seal. A key source for Varney seems to be A Survey of Hancock County by Samuel Wasson published by the Maine Board of Agriculture in 1878.

Conservation Values

The Preserve provides trails and open space near the village. The pond allows for ice skating in winter and a place for recreation and reflection throughout the year. The trails connect to Route One as well as the Point Road. Key attributes:

- 86 acres of forest and field is the third largest preserve on Crabtree Neck.

- The Ice Pond is a popular viewpoint and ice-skating pond in an area with few ponds.

- Forested wetlands provide watershed protection.

- Frontage on two roads provides multiple potential points of connection to trails.

Threats to Conservation

Spruce Budworm

The eastern spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) is a native insect that causes major damage to Maine’s spruce-fir forests on a regular cycle. Spruce budworm (SBW) caterpillars feed on the buds and needles of fir and spruces. Under normal (endemic) conditions populations of this insect are so low that SBW is hard to find. Periodically the budworm undergoes a population outbreak (epidemic) and becomes so abundant that serious feeding damage occurs. During epidemics defoliation is heavy enough that affected trees produce very little wood and many trees die. These outbreaks occur every 30 to 60 years. The Maine Forest Service has provided the following assessment based on data collected in 2019:

“Historical data tell us that Maine is due for another SBW outbreak and monitoring efforts illustrate that over the last several years, SBW population levels appear to have left the endemic or “stable” phase experienced between outbreak events. For several years now in Maine, both pheromone trap and light trap catches have been above numbers expected during the endemic phase and millions of acres of defoliation in neighboring Canadian provinces continues to encroach on the Maine border. Large in-flights of migrating moths from outbreak areas in Canada into northern Maine were well-documented in 2019. The impacts of these migration events on Maine’s forests remain to be seen. (MFS, 2020).”

If an outbreak occurs, because the Preserve is mostly spruce-fir forest, there is a significant risk of defoliation and tree loss.

Climate Change

The average annual temperature across Maine warmed by about 3.0 °F (1.7 °C) between 1895 and 2014. Since 1895, total annual precipitation has increased by about six inches (15 cm), or 13%, with most of the additional amount falling in summer and fall (Fernandez et al, 2015). These trends are expected to continue, with the region becoming warmer and wetter. However, some climate models predict drier summers (Janowiak, et al, 2018). Current modeling studies project that the dominant tree species in the region are likely to undergo dramatic range shifts as forests slowly adapt to changes in habitat conditions over the next 100 years. Projections suggest that suitable habitat for spruce-fir forests may virtually disappear from Maine in the next 100 years (Rustad et al, 2012). Under a low-emission scenario, habitat suitability will favor a transition to maple/beech/birch (northern hardwoods) forest, while oak and hickory trees would be favored under a high-emission scenario (Iverson et al, 2008). How forest composition will be affected by climatic changes will be influenced by many factors. The long life span of trees, the slowness with which they disperse, and the possibility that they may adapt genetically to changed climates all make it unclear how soon, if ever, trees will migrate to the places where the models say they should be (Rustad et al, 2012).

Fire

Periods of hot, dry weather occasionally lead to high forest fire risk in the region. The Preserve’s forest provides a substantial fuel source. Available fuel may increase if a spruce budworm epidemic defoliates and kills spruce and fir trees.

Red Pine Scale

Currently, the red pines on the Preserve are dying. Red pine scale, an exotic invasive insect has been spreading through the region and killed many red pines on Mount Desert Island in 2014. Fortunately, red pine is not an abundant species in the forests on Crabtree Neck and the red pine scale does not affect white pine or other tree species common to our forests. As a result, the loss of red pine trees in our preserves does not present a significant threat to conservation.

Permitted Activities

Permitted Activities

Hiking, snowshoeing, cross-country skiing, and ice skating are permitted during daylight hours. Dogs are permitted but must be kept under control. Hunting is not expressly prohibited, but is not encouraged due to the extensive trails and proximity to residences.

Restricted Activities

Motorized vehicles are strictly prohibited. No camping or fires are permitted. All trash, including pet and human base, must be carried out. No bicycling is permitted.

References

Johnson, Lois. 2016. Personal Communication, October, 2016.

Fernandez, I.J., C.V. Schmitt, S.D. Birkel, E. Stancioff, A.J. Pershing, J.T. Kelley, J.A. Runge, G.L. Jacobson, and P.A. Mayewski. 2015. Maine’s Climate Future: 2015 Update. Orono, ME: University of Maine. 24pp.

Foss, Thomas. 1870. A Brief Account of the Early Settlements Along the Shores of Skilling’s River.

Iverson, L.R., A.M. Prasad, S.N. Matthews, M. Peters. 2008. Estimating potential habitat for 134 eastern US tree species under six climate scenarios. Forest and Ecology Management. Volume 254, Issue 3, 10 February 2008, Pages 390–406

Janowiak, M.K., et al. 2018. New England and Northern Hew York Forest Ecosystem Vulnerability Assessment and Synthesis: A Report from the New England Climate Change Response Framework Project. USDA General Technical Report NRS-173.

Johnson, Lelia A. Clark. 1953. Sullivan and Sorrento Since 1760. Hancock County Publishing Company, Ellsworth, Maine.

Maine Forest Services (MFS), 2020. Spruce Budworm in Maine 2019. April 1, 2020.

Maine Historical Society, 2010. Maine History Online. Available at: https://www.mainememory.net/mho/; Accessed November, 2016.

Morehead, Warren, K. 1922. A Report on the Archaeology of Maine. Andover, MA.

Penobscot Marine Museum, 2012. Penobscot Bay History Online. Available at: http://penobscotmarinemuseum.org/pbho-1/; Accessed November, 2016.

Pope, Charles, H. 1906. A Pettingell Geneaology. Boston, MA.

Rustad, L., J. Campbell, J. S. Dukes, T. Huntington, K. F. Lambert, J. Mohan, and N. Rodenhouse. 2012. Changing Climate, Changing Forests: The Impacts of Climate Change on Forests of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada. USDA General Technical Report NRS-99.

SBW Task Force, 2016. Spruce Budworm. Available at: http://www.sprucebudwormmaine.org/; Accessed December, 2016.

Varney, Geo. J. 1886. History of Hancock Maine from A Gazetteer of the State of Maine, B.B. Russell, Boston. Wasson, Samuel. 1878. A Survey of Hancock County, Maine. Maine Board of Agriculture Survey. Augusta.

Click on any photo to enlarge and to see a slideshow